Earlier this month, distinguished college professor Angela Davis wrote an editorial about the anti-gang injunction proposed in the Fruitvale neighborhood.

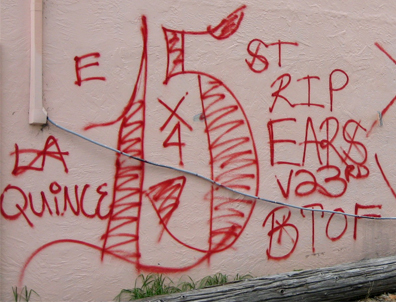

The injunction is designed to protect residents and businesses of the Fruitvale from the Norteños, one of the most violent and sophisticated criminal organizations in the city. In 2010 alone, this gang was connected to at least 38 shootings in Oakland – at least 13 of them in the Fruitvale area.

Unfortunately, much of Professor Davis’ opinion about Oakland’s anti-gang injunction policy is based on misinformation and an outdated ideology that allows no role for law enforcement in solving the serious problems we face in our city.

Professor Davis wrote: “For those who … simply live in the injunction zones, these injunctions transform the acts of approaching a vehicle, or communicating with a neighbor, into criminal acts.”

It’s a shocking claim, but categorically false. It’s also easily discredited by a quick read of the nine-page proposed injunction order on the City Attorney’s Web site (www.oaklandcityattorney.org).

On March 3, Professor Davis and other adults used this type of fearmongering to scare and anger students from the Fremont Federation schools who rallied at City Hall. They told the students that Oakland’s civil gang injunctions will suspend probable cause, legalize racial profiling, divert money away from schools, and as Davis wrote, “transform everyday actions into arrestable and punishable offenses” for anyone in designated areas.

Of course, Oakland’s injunctions don’t do any of those things. If they did, I would be the first to protest.

In Oakland, civil gang injunctions don’t give police any extraordinary power. They don’t suspend our legal protections, including those against racial profiling. And the police cannot simply apply them to anyone living in certain neighborhoods, as Davis falsely claims.

In reality, Oakland’s gang injunctions are narrowly tailored restraining orders against specific adults who are proven in court to be part of a criminal enterprise. The city’s first injunction in North Oakland only applies to 15 gang members based on their convictions for crimes including armed robbery, carjacking, carrying guns, drug dealing and domestic battery. In the Fruitvale, the order would apply to 40 men based largely on arrests and convictions for similar crimes.

In a specified area, enjoined gang members are restricted from carrying guns and threatening witnesses. They cannot associate in public or be on the street between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., with exceptions for things like work and social services. Defendants have the right to “opt-out” if they are no longer in the gang.

Davis’ op-ed also mistakenly claims that injunctions “divert” money away from other services. The amount spent on injunctions so far – just over $100,000 – comes from the City Attorney’s litigation budget, not from the budgets of any social or educational programs. This represents only a fraction of the money spent in Oakland on gang prevention programs, such as those funded by Measure Y, and it’s just a tiny part of the overall cost of law enforcement in the city.

Davis neglects to mention that the cost of investigating one homicide can outweigh the entire cost of an injunction case. If an injunction prevents one murder, it essentially pays for itself. Of course, it would also mean one less human being on the list of homicide victims this year.

I agree with Professor Davis that Oakland needs better intervention and more meaningful opportunities for young people. But we also need smart law enforcement. Chief Batts makes a powerful argument for using injunctions as one tool to focus on individuals responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime and violence in our city.

A “Radical Chic” 1960s ideology that sees police as the enemy of the people is not helpful to Oakland in 2011. Nor does it help for an academic of Davis’ standing to lecture Oakland students without first doing her own homework.